A few months ago, NamePros started observing aggressive credential stuffing attacks. This marked a new chapter in security at NamePros. We have rather secure infrastructure, especially for a site of our size. However, we've been growing at a steady pace, which makes us a bigger target.

The credential stuffing attacks we're observing are simple, yet they're difficult to block without your help. They don't compromise the security of NamePros itself, but they do mean that attackers are able to gain access to certain NamePros accounts that have made the mistake of using the same password on other (sometimes less secure) websites, and there's very little we can do to stop it. This may sound surprising or counterintuitive, but it all stems from one simple fact: most people use the same password everywhere.

Here's how a typical credential stuffing attack works:

NamePros isn't typically the target here, and this attack doesn't rely on weaknesses in NamePros' security, which makes it difficult for us to block.

This is especially problematic for a few reasons:

When the attacks picked up, we doubled-down on our game of cat-and-mouse. Our mitigations are quite thorough; a naïve attack is likely to fail. However, attackers have been getting more creative. They're spreading their attack out over large numbers of IP addresses to circumvent rate limiting. They're making login attempts from residential connections in the US rather than datacenters, presumably using compromised consumer devices. Some of the connections come from companies that provide cheap labor, hinting that the attacks may even be capable of passing captchas.

Initially, we could at least determine with a moderate degree of certainty which accounts were compromised. They were invariably old, inactive accounts with almost no data. As time went on, we started seeing a small number of active accounts targeted.

We notice these attacks because they're noisy. If we see thousands of suspicious login attempts over the span of an hour, we're going to dig deeper. Likewise, if someone reports that their account has been hacked, we'll investigate.

When this happens, it's not unusual for the same account to be hacked by multiple actors; after all, these passwords are floating around the internet for anyone to grab. If we know an account has been targeted, it's not hard to manually dig through their login history and pick out anything unusual, then branch out from there.

Sometimes the attacks are quite sneaky. Several months ago, a multi-day investigation revealed that one NamePros member was hijacking other members as far back as 2019. They managed to evade detection for quite some time, during which time they posted from both a hijacked account and their real account. They were careful enough that there was no reasonable way an automated system could have detected this; it required hours of careful research by a professional. More concerning are the accounts they accessed but didn't hijack: how long were they lurking, reading direct messages and other sensitive information?

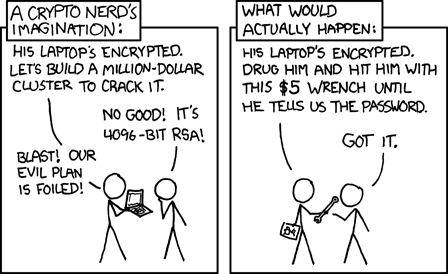

We can't combat this on our own--it's impossible. If someone knows your password and tries to log in from the same location as you, we have no way to tell that you've been hacked. We can block the majority of credential stuffing attempts, but some will inevitably slip through the cracks. The only real defense is to avoid using the same password across multiple websites.

Look, passwords are bad. Contrary to popular belief, if you can remember a password, it's a bad password. This is, of course, problematic: you are expected to remember your password, but if you do, it's a bad password, and you will get hacked. Various intelligent people have come up with fancy software known as "password managers" to get around this, although a simple paper notebook will suffice if you'd rather go that route. You need a random, unique password for every website. Not

Do you use the same password across multiple websites? Is your password

The credential stuffing attacks we're observing are simple, yet they're difficult to block without your help. They don't compromise the security of NamePros itself, but they do mean that attackers are able to gain access to certain NamePros accounts that have made the mistake of using the same password on other (sometimes less secure) websites, and there's very little we can do to stop it. This may sound surprising or counterintuitive, but it all stems from one simple fact: most people use the same password everywhere.

Here's how a typical credential stuffing attack works:

- Alice registers for an account at NamePros.com. She uses the same email address and password combination that she uses everywhere:

[email protected]andpassword123, respectively. - Another site on which Alice has an account, Acme.example, is compromised. Alice never realizes it, but the attackers abscond with her email address and password for Acme.example.

- Alice's email address and password are added to combo lists. These combo lists contain known email addresses and passwords for millions of users. They're distributed among hackers; sometimes in private marketplaces for a fee, sometimes publicly at no cost.

- Mallory, a hacker, obtains a combo list that contains Alice's username and password.

- Mallory uses automated tools to attempt to log into all the accounts in the combo list on NamePros.com.

- Most of the credentials don't work because they came from Acme.example, not NamePros.com. However, since Alice has an account at both websites with the same email address and password, Mallory successfully logs into Alice's account on the first attempt.

- Now that Mallory knows that Alice has poor security hygiene, in addition to gaining full access to Alice's NamePros account, Mallory can use the credentials on other websites that might be of interest to the a NamePros user. Registrar accounts are likely targets.

- Mallory uses the same credentials to log into Alice's registrar account and absconds with her domains.

NamePros isn't typically the target here, and this attack doesn't rely on weaknesses in NamePros' security, which makes it difficult for us to block.

This is especially problematic for a few reasons:

- As far as Alice is concerned, it makes little difference which website leaked her password. From her perspective, she's now lost her domains, her NamePros account, and possibly countless other valuable accounts. It's utterly devastating.

- NamePros can play a game of cat-and-mouse in an attempt to block some of the attacks, but that just encourages the attackers to be stealthier. Furthermore, it's not going to protect Alice's accounts elsewhere.

- If an attacker guesses Alice's password correctly on the first try, we may never even know that Alice was hacked, or it may take years to discover.

- NamePros itself isn't being hacked; we can't simply improve our security to stop these attacks.

When the attacks picked up, we doubled-down on our game of cat-and-mouse. Our mitigations are quite thorough; a naïve attack is likely to fail. However, attackers have been getting more creative. They're spreading their attack out over large numbers of IP addresses to circumvent rate limiting. They're making login attempts from residential connections in the US rather than datacenters, presumably using compromised consumer devices. Some of the connections come from companies that provide cheap labor, hinting that the attacks may even be capable of passing captchas.

Initially, we could at least determine with a moderate degree of certainty which accounts were compromised. They were invariably old, inactive accounts with almost no data. As time went on, we started seeing a small number of active accounts targeted.

We notice these attacks because they're noisy. If we see thousands of suspicious login attempts over the span of an hour, we're going to dig deeper. Likewise, if someone reports that their account has been hacked, we'll investigate.

When this happens, it's not unusual for the same account to be hacked by multiple actors; after all, these passwords are floating around the internet for anyone to grab. If we know an account has been targeted, it's not hard to manually dig through their login history and pick out anything unusual, then branch out from there.

Sometimes the attacks are quite sneaky. Several months ago, a multi-day investigation revealed that one NamePros member was hijacking other members as far back as 2019. They managed to evade detection for quite some time, during which time they posted from both a hijacked account and their real account. They were careful enough that there was no reasonable way an automated system could have detected this; it required hours of careful research by a professional. More concerning are the accounts they accessed but didn't hijack: how long were they lurking, reading direct messages and other sensitive information?

We can't combat this on our own--it's impossible. If someone knows your password and tries to log in from the same location as you, we have no way to tell that you've been hacked. We can block the majority of credential stuffing attempts, but some will inevitably slip through the cracks. The only real defense is to avoid using the same password across multiple websites.

Look, passwords are bad. Contrary to popular belief, if you can remember a password, it's a bad password. This is, of course, problematic: you are expected to remember your password, but if you do, it's a bad password, and you will get hacked. Various intelligent people have come up with fancy software known as "password managers" to get around this, although a simple paper notebook will suffice if you'd rather go that route. You need a random, unique password for every website. Not

mydogisawesome@7, not Ilik3gr##nEggz&Ham, not myCoolPassword!NamePros, not something even remotely similar to any other password you have ever used. Don't take my word for it; see what Bruce Schneier has to say on the matter. Security professionals are working hard to replace passwords with human-friendly alternatives, but, for now, we're stuck with passwords.Do you use the same password across multiple websites? Is your password

mydogisawesome@7? Stop. There's little we can do to protect an account with poor security hygiene; it will get hacked eventually. Everyone likes to think it won't happen to them, but it will. Are you willing to risk your NamePros account? Your domains? Your livelihood?